How Does One Test Acupuncture Against Placebo Anyway?

Acupuncture has some clinical applications beyond placebo, particularly in alleviating chronic pain, but there is no consistent evidence for its effectiveness beyond that.

Pinpointing The Usefulness Of Acupuncture

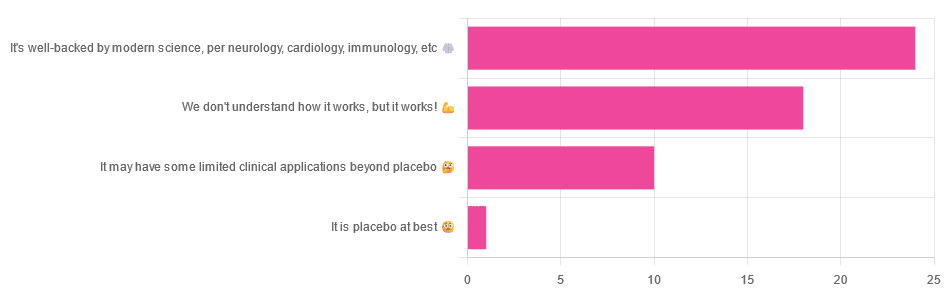

We asked you for your opinions on acupuncture, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of answers:

- A little under half of all respondents voted for “It’s well-backed by modern science, per neurology, cardiology, immunology, etc”

- Slightly fewer respondents voted for “We don’t understand how it works, but it works!”

- A little under a fifth of respondents voted for “It may have some limited clinical applications beyond placebo”

- One (1) respondent voted for for “It’s placebo at best”

When we did a main feature about homeopathy, a couple of subscribers wrote to say that they were confused as to what homeopathy was, so this time, we’ll start with a quick definition first.

First, what is acupuncture? For the convenience of a quick definition so that we can move on to the science, let’s borrow from Wikipedia:

❝Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine in which thin needles are inserted into the body.

Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientific knowledge, and it has been characterized as quackery.❞

Now, that’s not a promising start, but we will not be deterred! We will instead examine the science itself, rather than relying on tertiary sources like Wikipedia.

It’s worth noting before we move on, however, that there is vigorous debate behind the scenes of that article. The gist of the argument is:

- On one side: “Acupuncture is not pseudoscience/quackery! This has long been disproved and there are peer-reviewed research papers on the subject.”

- On the other: “Yes, but only in disreputable quack journals created specifically for that purpose”

The latter counterclaim is a) potentially a “no true Scotsman” rhetorical ploy b) potentially true regardless

Some counterclaims exhibit specific sinophobia, per “if the source is Chinese, don’t believe it”. That’s not helpful either.

Well, the waters sure are muddy. Where to begin? Let’s start with a relatively easy one:

It may have some clinical applications beyond placebo: True or False?

True! Admittedly, “may” is doing some of the heavy lifting here, but we’ll take what we can get to get us going.

One of the least controversial uses of acupuncture is to alleviate chronic pain. Dr. Vickers et al, in a study published under the auspices of JAMA (a very respectable journal, and based in the US, not China), found:

❝Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo.

However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture❞

Source: Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis

If you’re feeling sharp today, you may be wondering how the differences are described as “significant” and “relatively modest” in the same text. That’s because these words have different meanings in academic literature:

- Significant = p<0.05, where p is the probability of the achieved results occurring randomly

- Modest = the differences between the test group and the control group were small

In other words, “significant modest differences” means “the sample sizes were large, and the test group reliably got slightly better results than placebo”

We don’t understand how it works, but it works: True or False

Broadly False. When it works, we generally have an idea how.

Placebo is, of course, the main explanation. And even in examples such as the above, how is placebo acupuncture given?

By inserting acupuncture needles off-target rather than in accord with established meridians and points (the lines and dots that, per Traditional Chinese Medicine, indicate the flow of qi, our body’s vital energy, and welling-points of such).

So, if a patient feels that needles are being inserted randomly, they may no longer have the same confidence that they aren’t in the control group receiving placebo, which could explain the “modest” difference, without there being anything “to” acupuncture beyond placebo. After all, placebo works less well if you believe you are only receiving placebo!

Indeed, a (Korean, for the record) group of researchers wrote about this—and how this confounding factor cuts both ways:

❝Given the current research evidence that sham acupuncture can exert not only the originally expected non-specific effects but also sham acupuncture-specific effects, it would be misleading to simply regard sham acupuncture as the same as placebo.

Therefore, researchers should be cautious when using the term sham acupuncture in clinical investigations.❞

Source: Sham Acupuncture Is Not Just a Placebo

It’s well-backed by modern science, per neurology, cardiology, immunology, etc: True or False?

False, for the most part.

While yes, the meridians and points of acupuncture charts broadly correspond to nerves and vasculature, there is no evidence that inserting needles into those points does anything for one’s qi, itself a concept that has not made it into Western science—as a unified concept, anyway…

Note that our bodies are indeed full of energy. Electrical energy in our nerves, chemical energy in every living cell, kinetic energy in all our moving parts. Even, to stretch the point a bit, gravitational potential energy based on our mass.

All of these things could broadly be described as qi, if we so wish. Indeed, the ki in the Japanese martial art of aikido is the latter kinds; kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy based on our mass. Same goes, therefore for the ki in kiatsu, a kind of Japanese massage, while the ki in reiki, a Japanese spiritual healing practice, is rather more mystical.

The qi in Chinese qigong is mostly about oxygen, thus indirectly chemical energy, and the electrical energy of the nerves that are receiving oxygenated blood at higher or lower levels.

On the other hand, the efficacy of the use of acupuncture for various kinds of pain is well-enough evidenced. Indeed, even the UK’s famously thrifty NHS (that certainly would not spend money on something it did not find to work) offers it as a complementary therapy for some kinds of pain:

❝Western medical acupuncture (dry needling) is the use of acupuncture following a medical diagnosis. It involves stimulating sensory nerves under the skin and in the muscles.

This results in the body producing natural substances, such as pain-relieving endorphins. It’s likely that these naturally released substances are responsible for the beneficial effects experienced with acupuncture.❞

Source: NHS | Acupuncture

Meanwhile, the NIH’s National Cancer Institute recommends it… But not as a cancer treatment.

Rather, they recommend it as a complementary therapy for pain management, and also against nausea, for which there is also evidence that it can help.

Frustratingly, while they mention that there is lots of evidence for this, they don’t actually link the studies they’re citing, or give enough information to find them. Instead, they say things like “seven randomized clinical trials found that…” and provide links that look reassuring until one finds, upon clicking on them, that it’s just a link to the definition of “randomized clinical trial”:

Source: NIH | Nactional Cancer Institute | Acupuncture (PDQ®)–Patient Version

However, doing our own searches finds many studies (mostly in specialized, potentially biased, journals such as the Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies) finding significant modest outperformance of [what passes for] placebo.

Sometimes, the existence of papers with promising titles, and statements of how acupuncture might work for things other than relief of pain and nausea, hides the fact that the papers themselves do not, in fact, contain any evidence to support the hypothesis. Here’s an example:

❝The underlying mechanisms behind the benefits of acupuncture may be linked with the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (adrenal) axis and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and OPG/RANKL/RANK signaling pathways.

In summary, strong evidence may still come from prospective and well-designed clinical trials to shed light on the potential role of acupuncture in preserving bone loss❞

Source: Acupuncture for Osteoporosis: a Review of Its Clinical and Preclinical Studies

So, here they offered a very sciencey hypothesis, and to support that hypothesis, “strong evidence may still come”.

“We must keep faith” is not usually considered evidence worthy of inclusion in a paper!

PS: the above link is just to the abstract, because the “Full Text” link offered in that abstract leads to a completely unrelated article about HIV/AIDS-related cryptococcosis, in a completely different journal, nothing to do with acupuncture or osteoporosis).

Again, this is not the kind of professionalism we expect from peer-reviewed academic journals.

Bottom line:

Acupuncture reliably performs slightly better than sham acupuncture for the management of pain, and may also help against nausea.

Beyond placebo and the stimulation of endorphin release, there is no consistently reliable evidence that is has any other discernible medical effect by any mechanism known to Western science—though there are plenty of hypotheses.

That said, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and the logistical difficulty of testing acupuncture against placebo makes for slow research. Maybe one day we’ll know more.

For now:

- If you find it helps you: great! Enjoy 🙂

- If you think it might help you: try it! By a licensed professional with a good reputation, please.

- If you are not inclined to having needles put in you unnecessarily: skip it! Extant science suggests that at worst, you’ll be missing out on slight relief of pain/nausea.

Take care!

Share This Post

Learn To Grow

Sign up for weekly gardening tips, product reviews and discounts.